Hello friends,

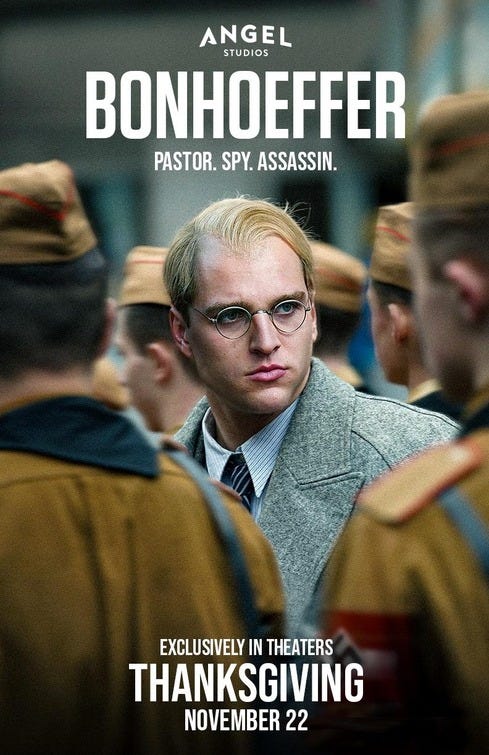

A couple weeks ago Sam and I went to watch the new movie about Dietrich Bonhoeffer with some friends from church—Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. I left the movie with a lot of thoughts I needed to process, so I decided to work them out through writing. I then sat on them for a couple weeks unsure if I should actually publish. (And also distracted by the fact that we just had a baby!)

Anyway, I decided to go ahead and share. I hope you find them helpful—or at the very least, thought-provoking.

I am by no means a Bonhoeffer scholar, but I have done some considerable deep dives on his life and work, having read numerous biographies as well as many of his own writings. His thought, especially on ethics, has deeply influenced me. With that in mind, I came into the movie a bit nervous about how the filmmakers would portray him.

You see, Bonhoeffer as a character is a bit of a Rorschach situation. People tend to look at his life and see what they want to see. Actually, a better metaphor might be a mirror, as most of the time, what they see is themselves. He has been hailed as a hero for liberal theologians, progressive activists, and evangelical apologists all at the same time—each group assuming he’s one of them.

It would be helpful, I think, to attempt to explain how we got to this place in discussions about Bonhoeffer generally. I’ll then lay out some of my problems with the movie just released—which I think doesn’t just get Bonhoeffer horribly wrong, but does it by sending a message I find deeply dangerous, especially in our current political climate.

How We Got Here

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a German pastor and theologian during the time of the Nazi regime. He is known for his profound theological writings and well as his resistance to the rise of Hitler. The point of his story most often emphasized is that he was an avowed pacifist who participated in a plot to assassinate Hitler. Participation which got him hanged, just weeks before the end of the war.

His story did not become popular for several decades. His good friend Eberhard Bethge published a biography of him in the 60s, but even after that, he was little known. Author Leon Howell lamented in the 90s that Bonhoeffer had not yet gained appropriate notoriety.

After Bethge’s biography, Bonhoeffer scholarship slowly progressed. As more people discovered who he was, he was hailed as a moral exemplar. In the 70s, Jesuit anti-war activist Daniel Berrigan viewed his work through the lens of Bonhoeffer, after having read Bethge’s biography while on the run from the FBI for destroying Vietnam draft records. Bonhoeffer was also praised by President George W. Bush in 2002 as “one of the greatest Germans of the twentieth century.”1

Things got more interesting, though, in 2010 when acclaimed author Eric Metaxas published his biography, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy, which became a best-seller and skyrocketed both Bonhoeffer’s and his own notoriety. I read this biography when it came out and, not knowing anything else about Bonhoeffer at the time, enjoyed it. Metaxas is an excellent writer and knows how to weave a complex narrative.

The problem is that, while it was quite well written and beloved by popular audiences, Bonhoeffer scholars skewered it in their reviews.2 They cited numerous factual errors (including misspellings of notorious German locations), “incomplete and garbled sources,” and an ignorance of, or antagonism toward, the robust scholarship up to the time.3 Writing as a conservative evangelical in the era of Obama, he cast the story of Bonhoeffer as one of his own.

For him, Bonhoeffer was an evangelical, certainly not a pacifist, and Metaxas was setting the record straight, liberating his story from the grasp of the “secular left,” and providing a moral example to stand up against what he considered an overreaching government. The problem was, he may have told a neat story, but it was not a story of the real Bonhoeffer.

Bonhoeffer was a complex human, which makes him both difficult to pin down and easy to mold to one’s liking. In reality, he was no evangelical. He doubted the virgin birth and the inerrancy of Scripture and had socialist-leaning political tendencies. But he was also not a paragon of progressive values. He was actually slow and often ambivalent in his response to the treatment of the Jews, and in the face of a growing movement for women’s ordination, failed to offer his support.4

The story of Bonhoeffer is not of a moral hero, but simply a good man doing his best.

As much as Metaxas would try to tell you otherwise5, Bonhoeffer was deeply committed to nonviolence, and the interesting part of his participation in the assassination attempt is not that he was somehow heroic enough to “do what he had to do,” but that he was wrestling with how to follow the will of God in a world steeped in evil. His problem was not whether he had the courage to “stand up for his convictions,” but figuring out what God’s will was when the messiness of an evil world made every decision seem a wrong one.

What the Movie Gets Wrong

And this is the central problem, I think, with this movie: there’s no uncertainty; there are no questions.

The movie Bonhoeffer never wonders whether what he is doing is right, but the real Bonhoeffer was deeply troubled by his participation. His role in the plot was small, to say the least, consisting merely of “using his church contacts in England to pass documents negotiating a possible peace treaty in the event the coup was successful.”6 But even this minimal participation troubled him, and he refused to justify it. In his view, he was taking a gamble, hoping that what he was doing was God’s will.7

Bonhoeffer wrote of the difficulty of applying our moral values, emphasizing that ethical judgments are made “in the middle,” where our criterion for good is often not directly applicable to the situation at hand. We rarely encounter good and evil in “pure” forms, where some ethical theory can clearly guide us to the right decision. In these moments, we simply must choose how to act, hoping that what we’re doing is right. And trusting that if it’s not, we can rely on the grace of God.8

In the movie, Bonhoeffer’s issue is not whether or not what he was doing was right, it was whether he had the courage to do it. And even in that, there was no hesitation.

Movie Bonhoeffer didn’t see a moral conundrum; he saw blood.

There’s a pivotal moment in the film where he is offered a role in the plot to assassinate the Fuhrer. He immediately agrees, even using the phrase, “Here I am. Send me,” as if he clearly saw a call from God to kill his enemy, and he was righteously willing to answer

He was challenged by Eberhard, who noted that he once said, “Christians must defeat their enemies with the power of love.”

“That was before Hitler,” he responds. Bethge challenges him, saying, “Is Hitler the first tyrant the world has seen?” And in the vein of a great old-western hero, Bonhoeffer shoots back, “He’s the first one I can stop.”

Not only does this exchange fly completely in the face of Bonhoeffer’s thoughtfully considered peace ethic, an ethic central to his faith and theology, but it casts Christian activism in terms that too easily justify violence. We only have to be like Jesus until the bad guy is bad enough; then, the Sermon on the Mount becomes fantasy, and we can take matters into our own hands.

The problem is that Bethge was right here. Hitler was not a singular evil. And when we can twist our faith as a call to violence if we perceive our enemy as “evil enough,” the justifications don’t stop.

The doctor performing abortions is not the first “murderer” in the world, but he’s the first one I can stop. The bigoted, right-wing government official is not the first oppressor in the world, but he’s the first I can stop.

(The greedy insurance CEO is not the first to exploit the needy, but he’s the first one I can stop…)

There’s a scene in the movie where Bonhoeffer is practicing a sermon in front of a friend, while cutting to clips of the assassination prep. At one moment, when speaking of the need for Christians to integrate both faith and action, on the word “action,” they cut to the suicide bomber strapping on his explosives.

The idea that the “action” we are called to as Christians is strapping bombs onto our bodies is absolutely horrific.

The movie was a call to arms, to embody your faith in violent action to thwart the bad guy. This is directly counter to Christ’s command to love our enemies, as well as the peace ethic Bonhoeffer was so committed to, stemming from that Christic command.

It’s also problematic in that the “bad guy” can be whoever we want it to be. As the character “Bonhoeffer” can and has been molded to support whatever cause a person supports, and “Hitler” can become a catchall for whatever group or leader you oppose, this movie is a rallying cry to defeat evil through violence, whatever you consider evil to be.

The movie leaves you not thinking about the insidious nature of evil and contemplating how to oppose it, but feeling spurred on to destroy who you already consider your enemy.

What we needed from this movie was not a push to ever more fanatical application of our ideologies, but a call to moral clarity. Our society is not short on people talking about “standing up” for what they believe in. We do, though, lack the necessary wisdom to discern our moment and the kind of Christ-like action that must take place. And we lack the humility to recognize, as the real Bonhoeffer did, that life in our world is infinitely complex and deeply meaningful. That every action is weighty and necessitates meticulous discernment.

If we don’t have the humility or wisdom to discern good and evil, our courage is mere extremism. In failing to capture the real Bonhoeffer and instead creating a firebrand fanatic with his name slapped on, the filmmakers add fuel to the extremist fires all too present in our society.

I’m with Mac Loftin in saying, this movie is not just bad; it’s dangerous.

As much as the movie wanted to cast Bonhoeffer as a hero, even a Christic one9, the character they created is no hero. And the real Bonhoeffer never sought to be one. As Bonhoeffer scholar Victoria Barnett noted:

In such moments we shouldn’t read Bonhoeffer for superficial sound bites or empty reassurances of larger-than-life heroism. We should read him because his is the story of one decent human being who understood better than any of us that in evil times, we must remain faithful—if only for the sake of future generations, because we are creating for them the foundation from which they can do good in this fallen world.

She quotes a portion of a letter he wrote in 1942, where he writes:

The ultimately responsible question is not how I extricate myself heroically from a situation, but how a coming generation is to go on living.10

That, too, is the question for us.

Haynes, Stephen R. The Battle for Bonhoeffer. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2018. Pg 1.

Metaxas, Eric. Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy. Thomas Nelson Inc, 2010. Pg 318.

Brock, Brian. Singing the Ethos of God: On the Place of Christian Ethics in Scripture. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007. Pg 90.

The final scene in the movie is Bonhoeffer’s execution, where he is hung in the middle of three nooses, an obvious allusion to Christ on the cross.